Black neighborhoods in Chicago targeted by high-interest loans

Pointing out that high-interest loans proliferate in non-white Chicago neighborhoods is a bit like saying the sky is blue or the grass is green, but a consumer group says it’s proving it for the first time with hard numbers.

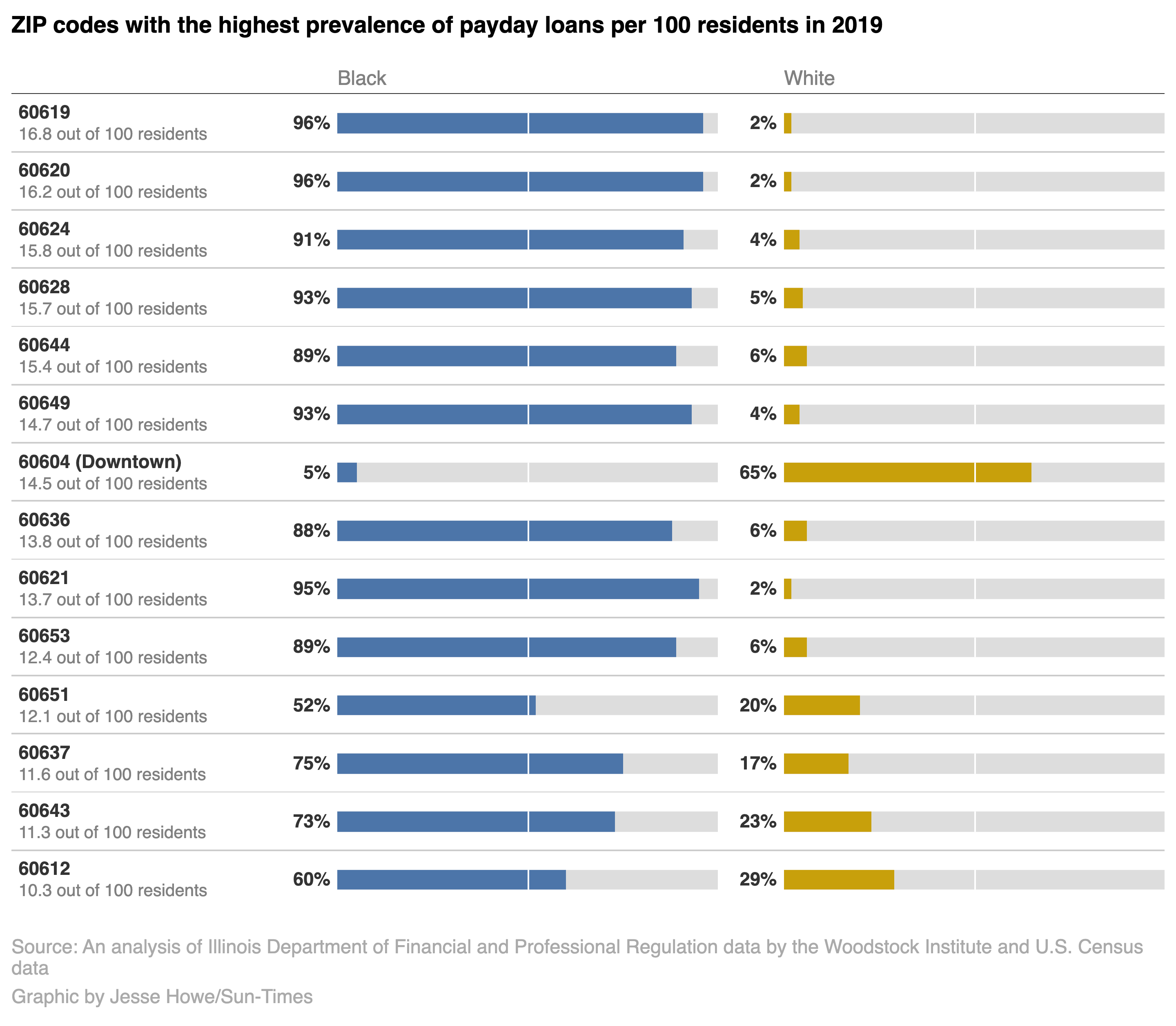

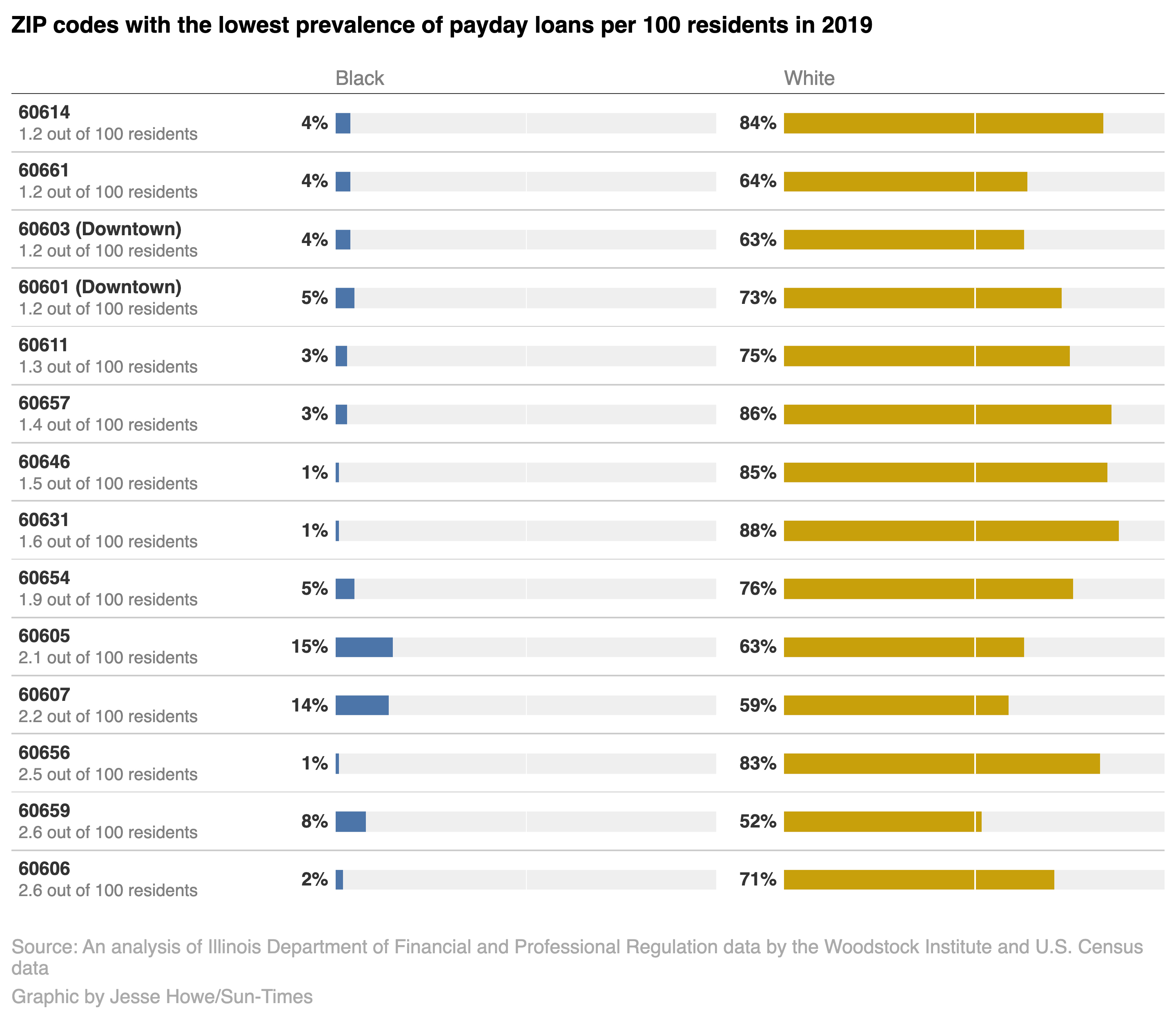

Using 2019 borrower loan data obtained from state regulators, the nonprofit Woodstock Institute found the top ZIP codes for payday loans, excluding the Loop, were majority-Black, including:

- 60619 and 60620 on the South Side, which include parts of Chatham, Burnside, Avalon Park and Greater Grand Crossing, Auburn Gresham and Washington Heights. Those ZIP codes had more than 16 payday loans per 100 people and are both 95.7{ac23b82de22bd478cde2a3afa9e55fd5f696f5668b46466ac4c8be2ee1b69550} Black.

- 60624 on the West Side, which includes parts of West Garfield Park, East Garfield Park and Humboldt Park and which had 15.8 payday loans per 100 people. That ZIP code covers an area that’s 90.7{ac23b82de22bd478cde2a3afa9e55fd5f696f5668b46466ac4c8be2ee1b69550} Black.

In contrast, ZIP codes with the lowest incidence of payday borrowers were mostly white, such as 60614 in Lincoln Park. That area had 1.1 payday loans per 100 people in a ZIP code that’s 84{ac23b82de22bd478cde2a3afa9e55fd5f696f5668b46466ac4c8be2ee1b69550} white.

The analysis included ZIP code data for borrowers with payday loans and payday installment loans, which largely disappeared as of March 23, when a new interest rate cap took effect in Illinois. The nonprofit group obtained the data through a records request to the Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation.

Data from 2020 — though a strange year for lending due to the COVID pandemic — was similar, with the top two ZIP codes 60619 and 60620, followed by 60628, which covers parts of Roseland, Pullman, West Pullman and Riverdale, and which is 93.1{ac23b82de22bd478cde2a3afa9e55fd5f696f5668b46466ac4c8be2ee1b69550} Black.

Brent Adams, senior vice president of the Woodstock Institute and IDFPR director under former Gov. Pat Quinn, called it “statistical significance on steroids.”

“These loans very specifically target Black communities,” Adams says, adding that high-interest lending perpetuates a status quo “that is riddled with racial and economic inequities.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23039090/Headshot_2019.jpg)

Studies have shown Black Americans have an average net worth that’s about one-tenth that of white Americans, largely due to past discriminatory practices that hindered the accumulation of family wealth, including denial of home mortgages.

The industry says it provides a necessary service for people who don’t have the credit history or collateral to qualify for traditional bank loans.

In Illinois, as of March 23, payday loans, title loans and installment loans must abide by a 36{ac23b82de22bd478cde2a3afa9e55fd5f696f5668b46466ac4c8be2ee1b69550} cap on the annual percentage rate of interest. The Illinois Predatory Loan Prevention Act also forces vehicle financing to adhere to the cap.

Tiffany Moore of Forest Park turned to an installment lender for the first time when the coronavirus hit and a tenant at her investment property couldn’t make rent. Her loan, for $9,500, had a term of five years and an interest rate of 35.989{ac23b82de22bd478cde2a3afa9e55fd5f696f5668b46466ac4c8be2ee1b69550}.

Even with a rate under 36{ac23b82de22bd478cde2a3afa9e55fd5f696f5668b46466ac4c8be2ee1b69550}, she realized she’d be paying back more than twice what she borrowed. So Moore paid it off early.

“I was like, I’ve got to get rid of this,” she says. “How can you get ahead if they’re charging all that interest?”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23039129/WATCHDOGS_11262021_6.jpg)

Ed D’Alessio, executive director of INFiN, a trade group that counts small-dollar lenders among its members, says the Woodstock analysis is “nothing more than a thought experiment that distracts from the real challenges facing borrowers today.”

D’Alessio says many borrowers are “underserved, overlooked or left behind by other financial institutions.”

The 36{ac23b82de22bd478cde2a3afa9e55fd5f696f5668b46466ac4c8be2ee1b69550} cap has already caused some payday and small-dollar lenders to shutter their Illinois locations, he says.

Samantha Carl of Palatine says the storefront lender she used in the suburbs has since closed. She got a $700 loan before the 36{ac23b82de22bd478cde2a3afa9e55fd5f696f5668b46466ac4c8be2ee1b69550} cap that had an APR of 399{ac23b82de22bd478cde2a3afa9e55fd5f696f5668b46466ac4c8be2ee1b69550}. She paid it off in a matter of months, but it still cost her about $1,200, she says.

“It helped when I needed it, but the interest rate is crazy,” says Carl, who relies on monthly disability checks and was hit with a sudden car repair.

Ed McFadden, spokesman for the American Financial Services Association, which represents installment lenders but does not include payday or auto title lenders, says the new law may have unintended consequences.

He points to a 2015 Federal Reserve survey in which lenders said they cannot break even on loans under $2,532 at 36{ac23b82de22bd478cde2a3afa9e55fd5f696f5668b46466ac4c8be2ee1b69550} APR.

“The rate cap may make policymakers and interest groups feel good about themselves, but it leaves many consumers who are already struggling out in a credit desert,” he says.

But Adams says there are alternatives, such as the Capital Good Fund, which lends to underserved consumers and charges an average interest rate of 13{ac23b82de22bd478cde2a3afa9e55fd5f696f5668b46466ac4c8be2ee1b69550}.