How schools teach Gen Z to make, manage money

When 17-year-old high school senior Rhyan Diaz started his cashiering job, he spent $3,000 in the first two months on clothes and other small items. He used to be “terrible with money,” he says.

Then he began taking a personal finance class at Canyon High School in Santa Clarita, California. Now he budgets meticulously to save for college — and eventually, a down payment on a house. “So I don’t have to struggle as much,” Diaz says. “I have seen my family struggle with certain things and almost wanting to give more but not having enough to give.”

Diaz is among the growing number of teens learning about money in school.

Rhyan Diaz says he was “terrible with money” before taking personal finance at Canyon High School.

Helen Zhao | CNBC

During the 2020-21 academic year, 7 out of 10 public high school students had access to a full-semester of personal finance, as either an elective or graduation requirement, according to Next Gen Personal Finance. That’s up from 2 out of 3 the prior year.

The number of states that require or will soon require students to take a semester of personal finance has doubled in the last three years, from 5 to 11. As of early April, about 20 states are considering more than 40 bills promoting personal finance education, according to NGPF.

“We’re creating a wave right? Of action and motion across the country,” says Yanely Espinal, NGPF director of education outreach, who as a Miami resident, played a major role in Florida signing into law this spring a new bill mandating personal finance education in high school.

Diaz meticulously tracks his expenses using a budgeting notebook.

Helen Zhao | CNBC

“It’s going to be slow progress with the 12th, 13th, 14th, 15th state,” she says. “But then progress will become a lot more rapid. By the time we have 30 states requiring this, then your state is embarrassed to be left behind.”

Even more movement is happening at the local level: The last school year marked the first time more students were required to take a semester-long personal finance class in states that don’t mandate it than in states that do, according to NGPF. That’s thanks to passionate community stakeholders.

Explaining to students how choices can help ‘make you a millionaire’

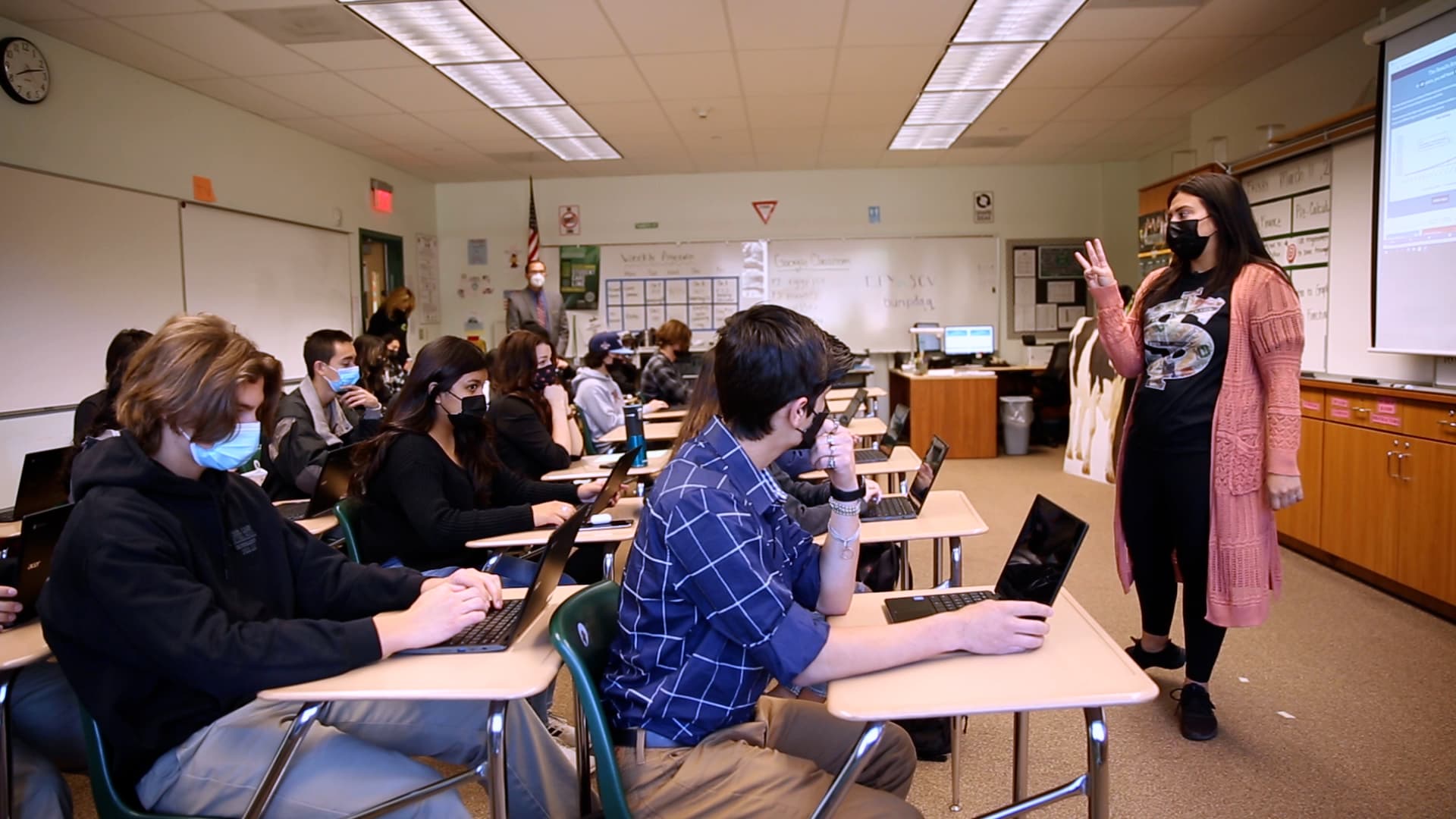

Diaz and the other 17- and 18-year-old seniors I met at Canyon High School in Santa Clarita, California, are already making strides toward short-term and long-term financial goals. They’re learning about saving, budgeting, debt, investing, careers, and more.

Dahlia Aldaz says learning about budgeting has been the most life-changing for her. For instance, she stopped spending $35 every other day at Starbucks, to save up for a car.

Joseph Rendon says he recently spent $400 in one month on dining out. Now he’s saving more so he can one day invest in stocks and cryptocurrency. “It’s basically passive income,” he says. “Your money is working for you.”

Dahlia Aldaz says learning about budgeting has had the greatest impact on her financial habits.

Helen Zhao | CNBC

Since I was bad with money until my mid-twenties, never saved for future goals and only recently considered investing, I was impressed by what I witnessed in their class.

I was present as the students’ teacher, Marina White, demonstrated the power of investing and compound interest. “This one decision, to give up a couple Starbucks every weekend and each morning you walk in here, can make you a millionaire by the time you retire,” she says.

Many of White’s students are “in shock” when they learn that their behavior and choices can so strongly influence their financial future.

Students work on a group assignment that demonstrates the power of long-term investing.

Helen Zhao | CNBC

The students I met are among the more than 4,700 seniors who have taken or are currently taking personal finance in the William Hart School District in Southern California, since the first class launched at Canyon High in 2015.

The course counts as one semester of math but is not required to graduate.

Communities fighting for personal finance education

What happened in the Hart district is a model for how personal finance education is increasingly spreading at a grassroots level, even when it’s not required by the state.

California is one of just three states, plus Washington, D.C., that do not include personal finance education in their K-12 standards, according to a 2022 report from the Council for Economic Education.

Statewide, under 1{ac23b82de22bd478cde2a3afa9e55fd5f696f5668b46466ac4c8be2ee1b69550} of students in California were required to take a semester of personal finance, during the 2020-21 academic year, according to NGPF. More than half of students in California learned personal finance as part of another course — usually for just a few weeks in an economics class. One in 5 had no access at all.

The 2020 to 2021 school year was the first in which more students were required to take personal finance in states that don’t mandate it, than in states that do.

Next Gen Personal Finance

That’s why former Canyon High teacher Kim Arnold and local personal finance coach Brendie Heter took matters into their own hands.

Concerned about her students being crippled by college debt, Arnold persuaded school and district administrators to let her start a personal finance class. The problem was, she says there was no money in the school or district budget to fund the course.

That’s when Arnold was introduced to Heter, who was already championing personal finance education at Santa Clarita schools. “But being an outsider, no one she talked to at the district office or at several of the schools she had called was interested,” Arnold said. “She needed me, and I needed her.”

Marina White teaches Canyon High seniors a lesson on investing and the power of compound interest.

Helen Zhao | CNBC

To start a personal finance class at Canyon High, Heter donated the $2,000 necessary for the curriculum and textbooks.

“Rumors spread fast,” Heter says. “Students were having a great time in class. They took the information back to their parents. Their parents started talking to their friends and their friends started asking each other, ‘Well, why doesn’t my son or daughter have this at this school?’ And we started getting calls almost every single day or weekly from parents all over.”

Funding classes at the district’s eight other high schools was a team effort. The Hart district provided about $19,000. The Heter family and another donor, real estate agent Sam Neylan, donated about $18,000. Arnold also secured a grant of around $10,000.

“I’m hoping that my district will be a beacon for the rest of the state,” Heter says.

‘Status quo is very powerful thing when it comes to public education policy’

Studies by numerous economists show that financial education improves financial outcomes: Credit scores increase, non-student debt falls, student loan repayment increases, and credit card delinquencies drop.

Still, changing the education system is far from easy. “Status quo is very powerful thing when it comes to public education policy,” says California Senate Minority Leader Scott Wilk, who previously served as vice chair of the CA Senate Education Committee.

One of the challenges is that high schools are in the business of preparing students for college — traditionally the surest path to the American dream.

“Schools’ funding is based on their attendance. So they want to make sure that they attract students to their schools, and at the high school level, that means providing lots of AP courses,” says Joshua Mitton, director of programs at the California Council on Economic Education. “Versus thinking about how can we, as a public education system, prepare students for the rest of their lives, whether or not they go on to college?”

These students are among the 4,700 seniors who have taken or are currently taking personal finance in the William Hart School District in Southern California.

Helen Zhao | CNBC

Personal finance faces competition from other subjects vying to establish a permanent place in the school curriculum, each of which has its own passionate constituency. Think classes on mental health, geography, ethnic studies, and nutrition, among others.

“Everyone wants a piece of the school curriculum,” says Richard Ingersoll, a professor of education and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. “We’ve had a century of adding things onto what we want schools to teach, all of which is completely worthwhile.”

And when you require a new course, something else often has got to go, because there just aren’t enough hours in the school day. Then you’ve got backlash. “There’s already people who have a have a vested interest in it. So you’re rolling the boulder uphill, all the time,” says Wilk.

Requiring a new course can also be costly. For example, California will soon require students to take a semester of ethnic studies. The state estimates it could cost more than $270 million each year.

Still, Wilk says the cost of personal finance education would be worth it. “If people are financially literate, they’re going to make better choices,” he says. “They’re not going to be a drag on greater society. And we’ll give them the tools to work to build wealth for themselves.”

More from Grow: